Last year I spent a couple of days visiting a friend in Frankfurt. During this visit, I sat in on a class run by Michael Krebber at the local art school. Krebber is an artist known for his ambivalent, ironic and relatively antagonistic position, and his classes are known for being quite loose and free-form. In the one that I attended, he read some magazine articles out loud to the students. He stopped from sentence to sentence to ask questions about certain references—the meaning of the term horizontality, and so forth. Reading further, the article mentioned the artist Tacita Dean. This prompted another refrain, where Krebber was reminded of ‘Research Hell,’ a term, he chuckled, he uses with his friends in Cologne.

I would consider, in this context, that the term Research Hell refers to the experience of the artist who equates research with quality, as a mark of credibility, seeking to validate a conceptual position through a gruelling, endless hunt for facts—when all they can truly know is the self-appointed prison of Research Hell.

Let’s step back a little. What is research? Research is the investigation of limited or unlimited aspects of a referent, be it thing, action or idea. It is undertaken to increase or develop knowledge about the subject. Research is a fundamental component of many artistic practices. It can provide a legible framework for real-world validation. Real-world validation: a variably-scaled situation of consensus, where an artwork (and by extension, the artist) is not only accepted, but also seen to be somehow valuable.

So why is artistic research so problematic? It is problematic because art is an absurd field in which to make a living. It is all construction and speculation. In this field, research—an index of the objective—is employed towards the ‘construction’ aspect of the equation. Once research has been conducted, a process of aestheticisation takes place, a demonstratively superficial turn of ambiguity and abstraction. It entails the grinding of poetry out of a reference, lifted from its semantic environment, reconfigured to do ‘new work’ that reflects on its source.

Now let us consider another German approach to ambivalence: that of Andreas Slominski. Slominski is an artist best known for taking a basic premise and executing it in an impossibly complex method. I recently showed a German friend some sculptures which looked like cardboard boxes but were actually steel frames with painted plastic walls. ‘Ah, the Slomi-way!’ he called it. The Slomi-way: to make a simple thing infinitely more complicated than it needs to be in order to illustrate the pathetic absurdity of the thing’s construction.

This is the strategy of exaggeration as critique. Let us keep this strategy in mind.

After leaving Frankfurt, I continued to think about this term Research Hell. The constant paranoid search for more details; bigger authentic knowledge on whatever topic; a web of reference so honed and complete that nobody could question the work’s deft incision.

‘Yes,’ I thought to myself. ‘Framework of real-world validation. Comical exaggeration to emphasise conceptual strategy. Fatalistic melancholy of assumed requirement. The expectations and anxieties of sophisticated dedication in the art field. The farce of this legitimising process in a profession that has a totally ambivalent relationship with anything empirical.’

These ideas were going through my head when I set out on the search for the source of Social Realism. The text below was written to accompany the subsequent exhibition of my research findings. It goes some way to explaining the mental and physical processes of the project.

European late-Summer 2012, returning to a small German apartment after a marathon in the club, reaching for a teabag, quiet mid-morning sun streaming through the courtyard window, a tin of sardines—Pan Do Mar, the Bread of the Sea—peered back from the shelf. Adorned with small sentimental sketches of fishermen plying their trade, the sardines were produced by a Spanish company specialising in organic and sustainable seafood products. In their engagement with traditional methods and values, the company gave their aesthetics over to that fine historical genre, Social Realism, with its echoes of better times gone by, the galvanising effect of people working together for people, the earnest belief in an ethically steadfast greater good. Honest, timeless and pure.

Where is Social Realism now?

Corralejo, touted as a sleepy traditional fishing village, at the northern tip of Fuerteventura in the Canary Islands; a Spanish colony one hundred kilometres off the coast of the Sahara Desert. A desolate volcanic landscape pushing all initiatives of industry, and nourishment, into the ocean. For hundreds of years, the water was the workplace.

Arriving in Corralejo, following a tenuous lead from an abstract ‘semantic treasure map’ on a sardine packet, it became quickly apparent that these traditional structures, the real-world referents of Social Realism, were not forthcoming. In their place, a highly developed tourism industry and a surfeit of abandoned real estate ventures, a combination of speculations gone right and wrong. No longer fixed in perpetual folklore, the town had been shaped by foreign influence and economic necessity. What value to be found in this scene? Where was the galvanising symbol, the crux of the social fabric?

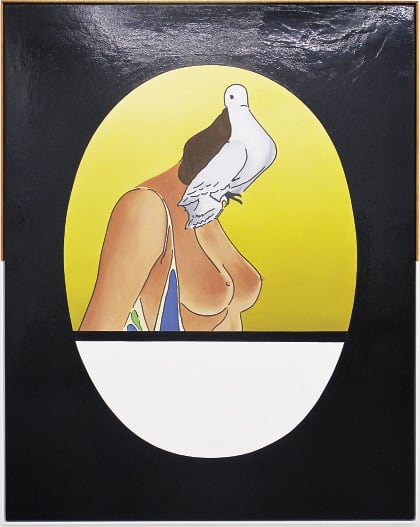

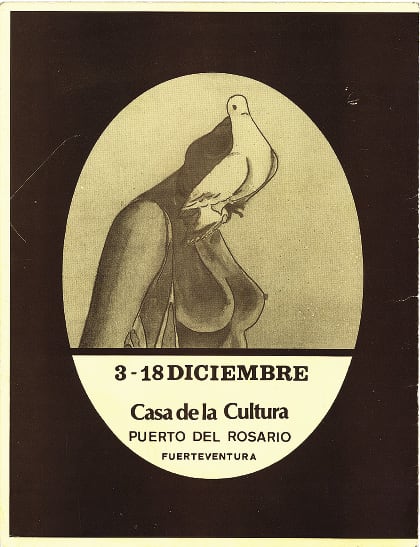

The buildings, stemming from Spanish architectural foundations, but tapered by available materials and temporal aesthetic mores, coming to rest at a pragmatic postmodernism. The shop signage, evidently repurposed as businesses launched and folded, designed to attract, yet speaking of a resourcefulness endemic to life on an island. The sincere expressions of the town artist, a role-fulfiller in the mould of Picasso, producing a stream of sexy-surreal local/fantasy landscapes from a beachfront studio on the edge of the village—‘the fringe of society’. The nature of international travel, movement and passage; an influx of European nationals, the British stalwarts and a growing Russian presence, and the emergent hybrid forms that cater to their needs; the land and the water all around, thoroughfare, isolation and connection; everything shipped in, permanent transition.

Social Realism is cliché, exaggeration, reduction and distillation, and it is always anchored in daily life. It must speak of greater truths, and it must present something to believe in. As a form with purpose, it suffers in its dogma, it thrives in its dynamism. It cannot be located: Social Realism is the index. Its counterpart—somewhere between openly universal and dramatically specific; always accessible and pedestrian, prosaic; stark, barren; honest, trapped of its time, and pure—Seaside Vernacular is the reality.

Ah, the Slomi-way! Over-doing it in service of credibility anxiety, research as a conspicuous performance, answering to the knowledge imperative, pointed/pointless. Paying silly money for flights, hotels, bad food and the blandest of cultural apocalypse, in the hope of unlocking the bogus non-clues of a can of fish: it was with no small joy that I undertook this doomed initiative.

What feelings might run concurrent to this project? Here are some words that could do: rigour, splendour, excess, idiocy, and the banal.

There was no new, important or significant knowledge produced. However, one cannot fault the rigour, which withstood the emphatic contradictions of a committed research project geared towards an abstract outcome. The meandering confusion littering the premise, the research, and the outcome, is entirely operative. But what foil for the dull tensions implicit in the transmission of the discursive into the realm of art object?

The joy of hermetic logic. By this, I mean the attendant happiness in the invention of a semantic circuit which allows the improbable (or indeed the ridiculous) to be elevated, made central. Nietzsche expands:

It gives us pleasure to turn experience into its opposite, to turn purposefulness into purposelessness, necessity into arbitrariness, in such a way that the process does not harm and is performed simply out of high spirits. For it frees us momentarily from the forces of necessity, purposefulness, and experience, in which we usually see our merciless masters.

Thus, this construction of abstract order is of an anti-authoritative thrust.

However: we are not clowns. If this operation of research, the development of a logic, and the production of artwork that follows from the process, is a pantomime, it is at least a veiled one. This veil might be considered the veil of earnestness. To enact artistic research is to ‘play doctors,’ to behave as if working under a series of consequential imperatives, all the while knowing that there is no consequence, no imperative, no risk or qualification at stake, bar those imagined or constructed for the occasion. But it should be noted, often in ‘the extended heat of the research moment,’ one comes quickly to believe in these imagined conditions, and so stress enters the field of play. Performed earnestness comes full circle, Earnest sneaks behind himself and grabs Play Earnest in a Real Chokehold!

This is the chokehold of responsibility, accountability, and the arbitrary amorphous spectre of new, important and significant knowledge.

In the face of this: bureaucratic penance, austere posturing as rapier riposte. In the interests of approval, self-indulgence, and the fraught private satisfaction of productive nihilism, the veneer of stoic refinement, in all its artifice, must be maintained.

Thomas Jeppe completed Honours in Cultural Studies in 2005. Confronted with the horrors of armchair academicism, he entered into cultural production.