The plane from which Michael Candy works is often aerial — survey-like. It pictures something bigger but acts from the micro. Having dedicated much of his life to engineering robots with a boy-wonder curiosity, the artist has recently developed his practice to encompass a critique of the more deftly social and political.

Employing mechanical quirks and not-so-out-of-place characters, his latest work, Ether Antenna latches onto the broad theme of environmental destruction and automation in religion. Screened at both the Kathmandu Triennale and at Bus Projects in 2017, the film follows robots that saunter through the polluted landscapes of Tibet, interacting with each other in faux-battles for the other’s skin. It’s dark, but not so much wry and ironic as saccharine sinister. One minute you’re laughing at the robots’ journeys, the next you’re in the deep realisation of the impacts of globalisation. Visually, the work references 1990s kids’ dramas, but brings that reference simultaneously to the technology-saturated present, and a deeply spiritual past — it’s pithy in its allusion to the automation of belief, but also respectful of the belief’s origins. It’s Sisyphus pushing that rock and inventing the wheel.

Can you please tell me about the process that you went through to make the video work, Ether Antenna, as part of the Kathmandu Triennale?

The purpose of my residency was to explore humanity’s spiritual synergy with machines. Looking to build some sort of roving vehicles to indefinitely travel through and co-inhabit traditional pilgrimage routes and areas of religious significance; introducing an almost gnostic new form of life into the complex social geography of Nepal.

When I went over, I was hosted by The Robotics Association of Nepal. I was hoping to collaborate and from there figure out what kind of tangent the project was going to take. The group turned out to be much more engineering-focused than anticipated, but from friendships gained mutually I found myself becoming embedded in the local arts scene, eventually leading to an invitation to return for the Kathmandu Triennale.

The project started as a series of visualisations and environments provoked by the astral soundscapes of Pauline Anna Strom’s ‘Trans-Millenia Consort’.1 Eventually I met Chelsea Wiebers, an American apprentice of Lok Chitrakar, ‘the last’ traditional Paubha painter of the Newa people of Kathmandu Valley. This guy can take up to sixteen years to finish a painting and seeing as Chelsea has only been there for four years I’m not sure she’d have seen one complete. She was fluent in Nepali and well versed in the cultural stories of Kathmandu valley. She became my conduit to Lok, and through them, we began to figure out a sort of narrative that I could work with.

The first day we met, I brought a copper Ankhora which I then automated into a sort or rolling hermit crab character.2 Unsure of whether this would offend or not, I powered it on in Chitrakar’s studio and it came to life rolling about the room. Lok and Chelsea both laughed and immediately grasped the nature of the project, and from there the ideas, narrative and physicality of the project quickly took form.

Can you give us more of a moving description of the video work’s narrative?

One of the things to note is that there’s a lot of Nepali text in the film as it was intended to be a Nepali film. Yet there’s only one scene of dialogue; one robot says ‘What is this?’ and the other says, ‘I don’t know’. It’s in there as a sort of icebreaker. It helped when we’d turn up to a village and pull out a screen and start projecting with no prior context. It made people relax, you know — the robot was going to poo; it’s not all serious.

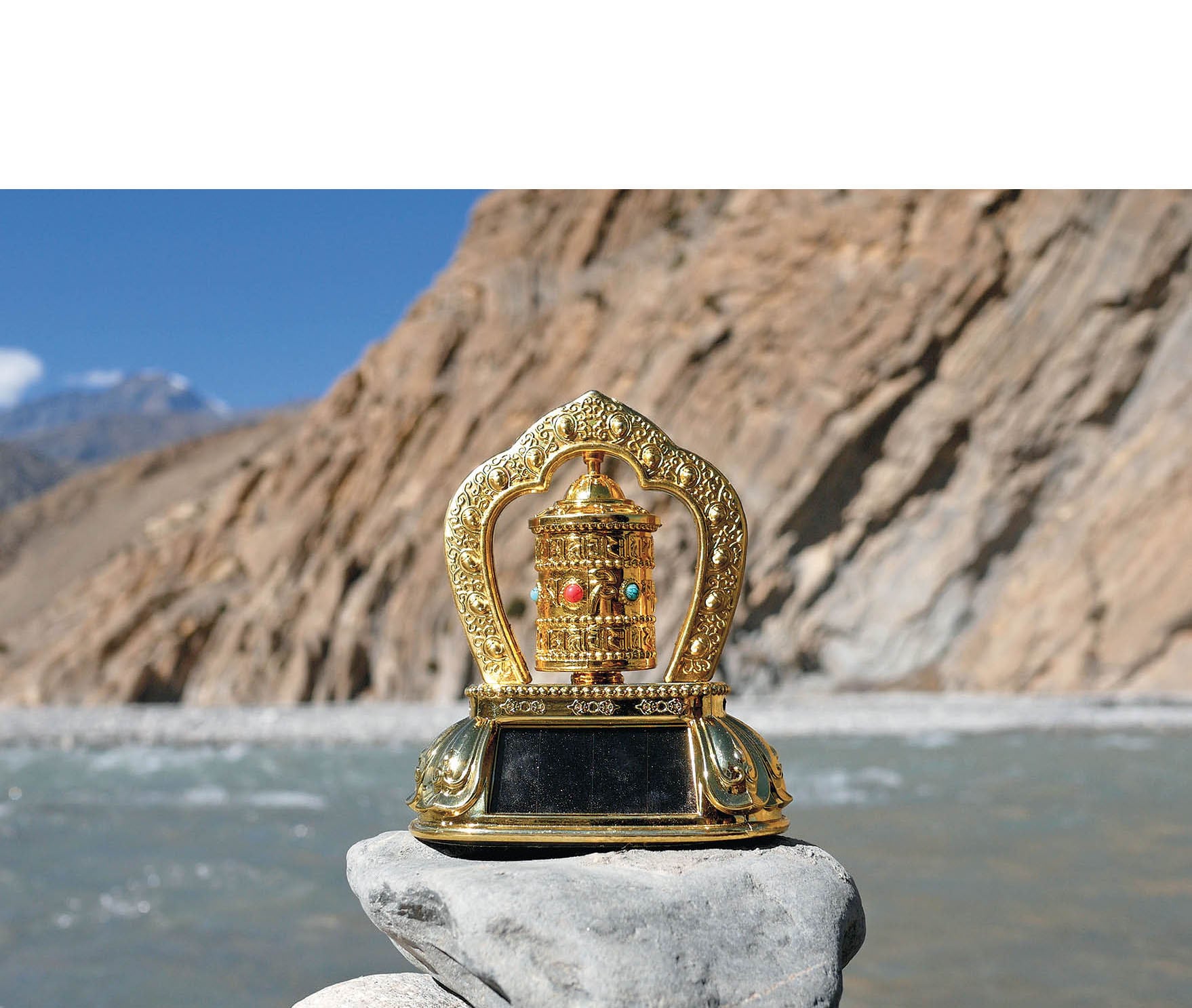

The film itself is in three parts, each chapter is divided by a solar powered prayer wheel within the chapter’s environment. Chapter one has the prayer wheel rotating clockwise as all pilgrimages are completed with the gods on your right side. In the second chapter everything is going wrong, thus the wheel is rotating backwards, and by the final chapter the wheel stands still as it rotates its body around itself. This chapter is set somewhere in the afterlife.

Why a robot?

The idea of automata originates in the mythologies of many cultures around the world. It’s an obvious outcome of a technology-enabled civilisation. As digital automation continues to penetrate our daily life, it’s easy to overlook the analogue counterparts and machines that have made modern living possible. As spirituality has always existed as a nexus between ecology and sociology, technology proves the perfect mediator.

In 2014, I traveled to Ladakh and spent a few weeks exploring the Indian Himalayas. One of the most striking things was to find ancient mechanical infrastructure still functioning and still relevant in their society. None of those complex folding walls, trap doors or snake pits that Hollywood seems so fond of would ever function without a good amount of oil and snake food. But here, in the Himalayas, you can find and touch a several-hundred-year-old spinning drum embossed with text. With the flick of a finger, it will pray for you; some of these contraptions use water, wind or solar to complete their eternal journey clockwise.

Nowadays you can’t catch a taxi in Kathmandu without a plastic solar powered prayer wheel whirling away on the dash. For me, these are simple machines doing man’s spiritual bidding. Ether machines keeping you connected to the cloud, from a time when people actually knew where the cloud was.

What is the significance of the film’s reference to Buddhist tales?

Though just over ten per cent of the population in Nepal is actually Buddhist, Buddha was born in Shakya which lies in present day Nepal. Through a diverse history of kingdoms, civil wars and upheavals, Nepal’s religious past has shifted a multitude of times, and this shows as some temples have Buddhist statues replaced with Hindu gods. However, Hindus share a couple of gods with Buddhists, so people apparently continued to pray to their religion of choice in secret.

The film is loosely based on some Buddhist tales as it is ever more appropriate to explore the most ancient documented beliefs of Nepal with modern technology. This is owing to Kathmandu’s rapid development into a techno-metropolis. Contrary to this, the scene where the Ankhoras are birthed from a tree in the temple garden of Muktinath, is sacred for being a place of worship for both Hindus and Buddhists. This was filmed at 3,710 metres above sea level and also happened to be where my travel partner experienced severe altitude sickness.

How did you work with the local community in Kathmandu?

I had the opportunity to do a workshop and presentation which lead to a lot of people inviting me places including a school and a non-government organisation orphanage. The robots were always a good icebreaker when we couldn’t communicate; kids in particular tended to develop an immediate empathy for the robots, identifying with them more as characters than machines.

Most of the city scenes took place in severely polluted areas of the riverbank, which unfortunately also exist as temporary housing establishments for earthquake victims and ‘lower caste’ alike.

One shot took place in a small polluted creek. The locals crowded around as I setup to film a prayer wheel floating on an island of trash. Without any type of communication, a young kid jumped down and repositioned the wheel on a plastic bucket so to position it better for the shot. For the next few hours he started tagging along, helping me film and move stuff as I was working near the river, we couldn’t talk but we seemed to understand each other.

We started filming one of the robots navigating the ruins of a temple, an open thoroughfare for the locals, after a couple of scenes two police officers came over and started yelling at him. There was some aggressive discussion between them which soon turned violent. Being a tourist in Asia it’s easy to overlook caste systems as you drive by the temporary settlements these people call home, but this confrontation came as a rude awakening.

When I returned a couple of months later for the Triennale, the presentation of Ether Antenna took the form of a mobile cinema. We shared a map online and tagged a series of slum areas including those where filming took place. Each night we would travel to location on scooters followed by a taxi full of PA gear. Most adults react when they see parts of their village on the screen, but it was the children who seemed to connect strongly with the robots as living things, allowing them to follow the plot closer and empathise with the victims. I’d often ask what they thought had happened and to my surprise it wasn’t ever too far from my intentions.

How do you think technology can consolidate with the spiritual? How has automation played a role in the way that religion can function, from your experience with the prayer wheels and these ancient forms of technology?

In a physical context, automation in religion makes sense. If all you have to do is spin a wheel to be religious, it frees up time for other things, such as working on your farm or studying. If you can have an App that can tell you which direction Mecca is, that saves you a lot of time looking for your compass and clock.

In 1973 Robert Metcalfe created the Ethernet, a now standard computer networking technology, named after a disproved physics problem called the luminiferous ether. Stating: ‘The whole concept of an omnipresent, completely passive-medium for the propagation of magnetic waves didn’t exist. It was fictional’.3

Most forms of religion refer to a governing power, the power of a god, one which you can only interact with through faith, trust and belief. This intangible interaction cannot be tethered to reality. Our new mythology is that of the Internet, and unfortunately it tends to have ever more real implications on our physical being than the old-school ether. It exists as a physical system yet tends to propagate disbelief … we finally have a network that can give back but it seems to be for all the wrong reasons.

Sarah Werkmeister is a writer, curator and broadcaster based in Melbourne. She currently holds positions with Shepparton Art Museum and Public Art Melbourne, and is undertaking her Masters of Art Curatorship. Her current research interest lies in the transference of social and political urgency to gallery and museum spaces.

remembers?page=2, accessed 14 June 2017.