Mish Grigor

The Talk

Performance Space

2–5 November 2016

My uncle first told my mother he was HIV positive in 1983, the same year I was born. For many in East Sydney in the early 1980s, diagnosis meant death. For my uncle, this did not come as quickly as for many, mercifully; he died of AIDS related complications in August 2014, as full of humour, opinions and guts as the day I was born. My mother describes those early days as terrifying, the world seized with a ‘terrible, visceral fear of infection’. It was an anxious period. Anxious and strangely silent.

After seeing Mish Grigor’s The Talk at Performance Space’s Liveworks Festival in late 2016, I asked Mum if my uncle was out to everyone and the answer was quick and definitive: ‘absolutely not’. ‘It all stays in the family. You lock away those intimacies’. ‘He would have lost his job… My father never related to him the same way again’, she told me. ‘I never would have revealed his sexuality’. Years later she published a story about sewing a panel for an AIDS quilt in an anthology of fiction. She did not use my uncle’s name.

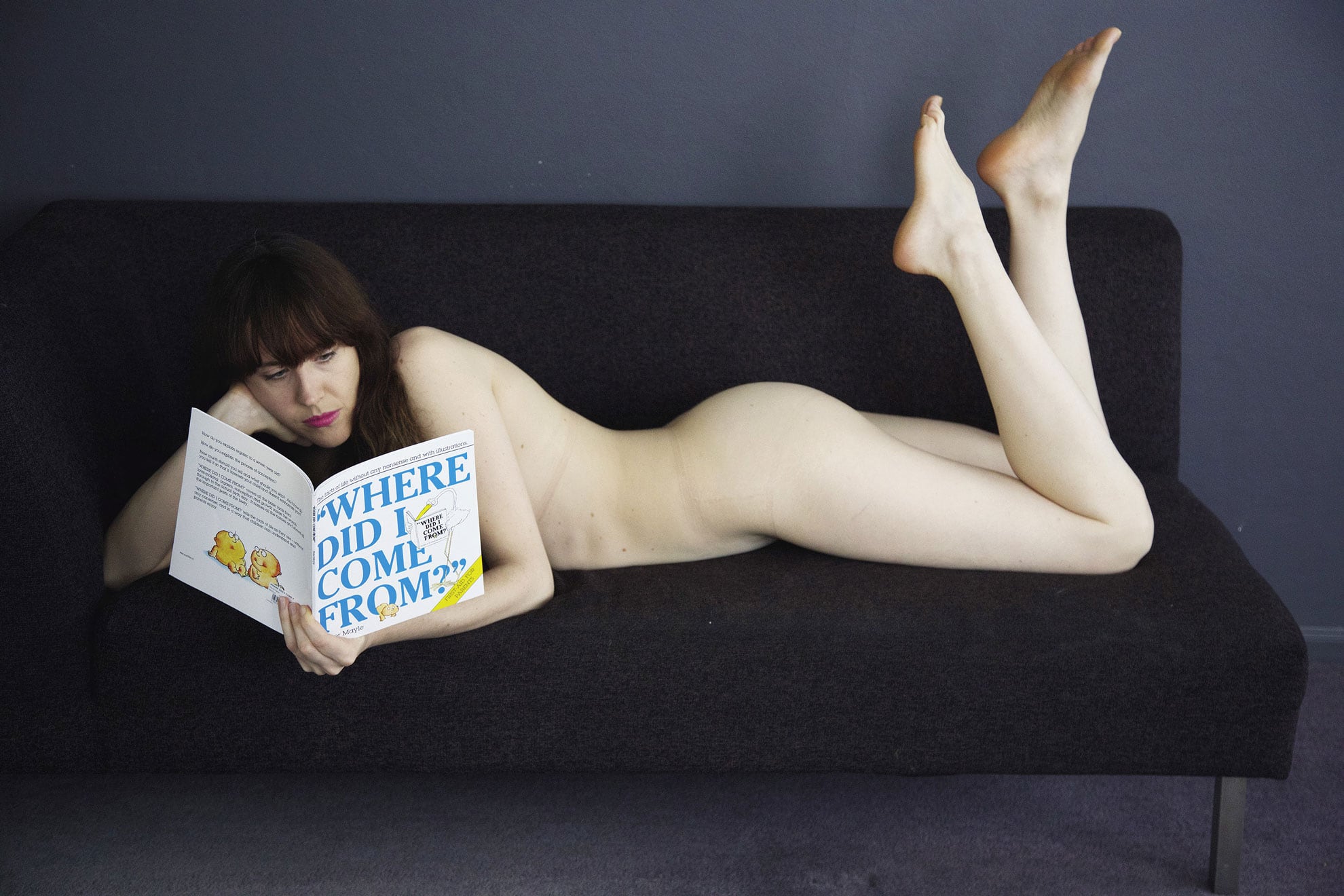

A little over fourteen months earlier I was sitting opposite Mish in the Art Gallery of Western Australia, elevated a little above the floor on a large plinth and wearing a cheap blond wig. This work was called Sex Talk and involved audiences reading transcripts of Mish (playing herself) and her family (played by whomever was opposite her) discussing sex. Sex Talk was an early version of The Talk. As part of Proximity Festival, the work was a one-on-one performance — one audience member would read opposite Mish with no other onlookers, lending the whole festival a sort of conspiratorial air. Each performance was a secret shared, an intimacy, a conversation. At Liveworks, the full script (about an hour) was performed by Mish and a rotating cast of audience members, developed from these earlier transcripts.

The interviews were inspired by her brother’s coming out, first as gay — and then as HIV positive. This second reveal was a poignant moment, a sombre break in what audiences could have thought, until that point, was an awkward familial sex comedy. As Mish recounted her response to her brother’s confession — to share embarrassing stories from her sexual past to assuage the questions her brother endured about his sex life — I tried to remember how my mother told me about my uncle’s status as a child. Most of what I recall is learning the litany of the ways in which AIDS is not transmitted: kissing, drinking from glasses, sharing food, hugging. I also remember my acute consciousness to continue to perform these actions: kissing my uncle on the lips, offering food from my plate, cuddling close.

Like Mish, I responded by performing gestures of inclusion, occasionally accompanied by shame if I caught myself hesitating in these acts of intimacy. There is a moment in The Talk where Mish describes a similar experience after her brother cut himself cooking, and it broke my heart: shame is a powerful affect. Indeed, much of my initial response to The Talk was one of immense familiarity and poignancy. It also prompted me to ask my mother about when my uncle came out to her for the first time, and we spoke at length that day, about my uncle and about my own coming out (which we’d never really discussed either: the strange silence of queerness marches on).

I think Mum hit the nail on the head while I was describing the work to her in our talk. ‘It’s a probing of what’s taboo’, she said. ‘Is it worse that her brother is HIV positive or that she’s done all these things she’s describing?’ (this in response to my recounting of a scene where Mish describes repeatedly losing condoms inside her after sex). ‘Or’, she added, ‘is it worse that she’s using these family stories to make a successful theatre show?’ The Talk is indeed about taboo, the conversations we have with each other and those we do not; the public and the private faces we wear; what we see and hear and what is silenced and hidden; what the costs of these states of (in)visibility are.

All these things played on my mind as I considered how to write this text. I could have talked about how the experience differed between Proximity and Liveworks and the different modes of complicity that these two stagings evoked. I could have talked about the act of interview and transcription as a communicative mode; the care involved in spending an average of four times as many minutes transcribing a conversation as having it in the first place, and the nature of ‘verbatim’ theatre and its different expressions. I could have critiqued the arguably very Western construct where theatre becomes a kind of therapy, the confessional model.

A central question I find myself coming back to however is: was any of it true? How much of it was true? And, do I care if it was true? Early in the piece, Mish casually told us that her family asked her not to include certain details, not to use their names, not to keep going with the interviews. ‘I didn’t do that’, she said, relating to us their anger and refusal to see the show. Much of the work was wrapped up in this moment. What does it mean to make an audience complicit in not only bearing witness to, but in literally enacting this apparent transgression? The Talk was certainly about transgression; about veracity and what constitutes truth; about the power of fiction to unsettle, and at times, transcend what we think of as truth; and the fickleness of this concept.

It is also about the white, Western communicative models that, again and again, silence the other (including queer and HIV-positive communities) and the importance of telling these stories (despite the costs): or to flip this. The privilege Mish enacted was apparently creating art at the expense of her family. For me, watching the work unfold over several iterations was immensely rewarding and the questions it raised critical. How important is the truth? What is the power of fiction? Who gets to speak and for whom? What do we consider taboo and why? What is the cost of silence?

Now more than ever, we need to talk. In her beguiling, humorous and always witty works, Mish succeeds to the extent to which she starts these conversations. And for me at least, The Talk has been the beginning of many.